Newton’s laws of motion are three physical laws that form the basis for classical mechanics. They describe the relationship between the

![English: William Blake's depiction of Isaac Ne... English: William Blake's depiction of Isaac Ne...]()

- English: William Blake’s depiction of Isaac Newton working on the principle of Divine Proportion (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

forces acting on a body and its motion due to those forces. They have been expressed in several different ways over nearly three centuries,[1] and can be summarized as follows:

-

First law: If an object experiences no net force, then its velocity is constant: the object is either at rest (if its velocity is zero), or it moves in a straight line with constant speed (if its velocity is nonzero).[2][3][4]

-

Second law: The acceleration a of a body is parallel and directly proportional to the net force F acting on the body, is in the direction of the net force, and is inversely proportional to the mass m of the body, i.e., F = ma.

-

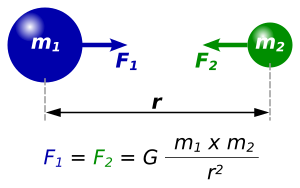

Third law: When a first body exerts a force F1 on a second body, the second body simultaneously exerts a force F2 = −F1 on the first body. This means thatF1 and F2 are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction.

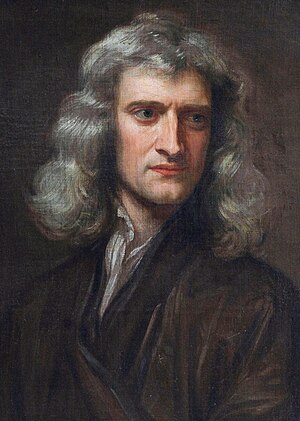

The three laws of motion were first compiled by Sir Isaac Newton in his work Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, first published in 1687.[5] Newton used them to explain and investigate the motion of many physical objects and systems.[6] For example, in the third volume of the text, Newton showed that these laws of motion, combined with his law of universal gravitation, explained Kepler’s laws of planetary motion.

Overview

English: Isaac Newton Dansk: Sir Isaac Newton Français : Newton (1642-1727) Bahasa Indonesia: Issac Newton saat berusia 46 tahun pada lukisan karya Godfrey Kneller tahun 1689 Lietuvių: Seras Izaokas Niutonas 1689-aisiais Македонски: Сер Исак Њутн на возраст од 46 години (1689) Nederlands: Newton geboren 4 januari 1643 Türkçe: Sir Isaac Newton. (ö. 20 Mart 1727) (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Isaac Newton (1643-1727), the physicist who formulated the laws

Newton’s laws are applied to bodies (objects) which are considered or idealized as a particle,[7] in the sense that the extent of the body is neglected in the evaluation of its motion, i.e., the object is small compared to the distances involved in the analysis, or the deformation and rotation of the body is of no importance in the analysis. Therefore, a planet can be idealized as a particle for analysis of its orbital motion around a star.

In their original form, Newton’s laws of motion are not adequate to characterize the motion of rigid bodies and deformable bodies. Leonard Euler in 1750 introduced a generalization of Newton’s laws of motion for rigid bodies called the Euler’s laws of motion, later applied as well for deformable bodies assumed as a continuum. If a body is represented as an assemblage of discrete particles, each governed by Newton’s laws of motion, then Euler’s laws can be derived from Newton’s laws. Euler’s laws can, however, be taken as axioms describing the laws of motion for extended bodies, independently of any particle structure.[8]

Newton’s laws hold only with respect to a certain set of frames of reference called Newtonian or inertial reference frames. Some authors interpret the first law as defining what an inertial reference frame is; from this point of view, the second law only holds when the observation is made from an inertial reference frame, and therefore the first law cannot be proved as a special case of the second. Other authors do treat the first law as a corollary of the second.[9][10] The explicit concept of an inertial frame of reference was not developed until long after Newton’s death.

In the given interpretation mass, acceleration, momentum, and (most importantly) force are assumed to be externally defined quantities. This is the most common, but not the only interpretation of the way one can consider the laws to be a definition of these quantities.

Newtonian mechanics has been superseded by special relativity, but it is still useful as an approximation when the speeds involved are much slower than the speed of light.[11]

Newton’s first law

Walter Lewin explains Newton’s first law and reference frames. (MIT Course 8.01)[12]

The first law law states that if the net force (the vector sum of all forces acting on an object) is zero, then the velocity of the object is constant. Velocity is a vector quantity which expresses both the object’s speed and the direction of its motion; therefore, the statement that the object’s velocity is constant is a statement that both its speed and the direction of its motion are constant.

The first law can be stated mathematically as

Consequently,

-

An object that is at rest will stay at rest unless an unbalanced force acts upon it.

-

An object that is in motion will not change its velocity unless an unbalanced force acts upon it. This is known as uniform motion.

An object continues to do whatever it happens to be doing unless a force is exerted upon it. If it is at rest, it continues in a state of rest (demonstrated when a tablecloth is skillfully whipped from under dishes on a tabletop and the dishes remain in their initial state of rest). If an object is moving, it continues to move without turning or changing its speed. This is evident in space probes that continually move in outer space. Changes in motion must be imposed against the tendency of an object to retain its state of motion. In the absence of net forces, a moving object tends to move along a straight line path indefinitely.

Newton placed the first law of motion to establish frames of reference for which the other laws are applicable. The first law of motion postulates the existence of at least one frame of reference called a Newtonian or inertial reference frame, relative to which the motion of a particle not subject to forces is a straight line at a constant speed.[9][13] Newton’s first law is often referred to as the law of inertia. Thus, a condition necessary for the uniform motion of a particle relative to an inertial reference frame is that the total net force acting on it is zero. In this sense, the first law can be restated as:

In every material universe, the motion of a particle in a preferential reference frame Φ is determined by the action of forces whose total vanished for all times when and only when the velocity of the particle is constant in Φ. That is, a particle initially at rest or in uniform motion in the preferential frame Φ continues in that state unless compelled by forces to change it.[14]

Newton’s laws are valid only in an inertial reference frame. Any reference frame that is in uniform motion with respect to an inertial frame is also an inertial frame, i.e. Galilean invariance or the principle of Newtonian relativity.[15]

![Newton's law of universal gravitation for two ... Newton's law of universal gravitation for two ...]()

- Newton’s law of universal gravitation for two bodies. This law governs gravitational forces in the Earth. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

History

From the original Latin of Newton’s Principia:

“ |

Lex I: Corpus omne perseverare in statu suo quiescendi vel movendi uniformiter in directum, nisi quatenus a viribus impressis cogitur statum illum mutare. |

” |

Translated to English, this reads:

“ |

Law I: Every body persists in its state of being at rest or of moving uniformly straight forward, except insofar as it is compelled to change its state by force impressed.[16] |

” |

Aristotle had the view that all objects have a natural place in the universe: that heavy objects (such as rocks) wanted to be at rest on the Earth and that light objects like smoke wanted to be at rest in the sky and the stars wanted to remain in the heavens. He thought that a body was in its natural state when it was at rest, and for the body to move in a straight line at a constant speed an external agent was needed to continually propel it, otherwise it would stop moving. Galileo Galilei, however, realized that a force is necessary to change the velocity of a body, i.e., acceleration, but no force is needed to maintain its velocity. In other words, Galileo stated that, in the absence of a force, a moving object will continue moving. The tendency of objects to resist changes in motion was what Galileo called inertia. This insight was refined by Newton, who made it into his first law, also known as the “law of inertia”—no force means no acceleration, and hence the body will maintain its velocity. As Newton’s first law is a restatement of the law of inertia which Galileo had already described, Newton appropriately gave credit to Galileo.

The law of inertia apparently occurred to several different natural philosophers and scientists independently, including Thomas Hobbes in his Leviathan.[17] The 17th century philosopher René Descartes also formulated the law, although he did not perform any experiments to confirm it.

Newton’s second law

Walter Lewin explains Newton’s second law, using gravity as an example. (MIT OCW)[18]

Explanation

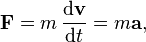

The second law states that the net force on an object is equal to the rate of change (that is, the derivative) of its linear momentum p in an inertial reference frame:

The second law can also be stated in terms of an object’s acceleration. Since the law is valid only for constant-mass systems,[19][20][21] the mass can be taken outside the differentiation operator by the constant factor rule in differentiation. Thus,

where F is the net force applied, m is the mass of the body, and a is the body’s acceleration. Thus, the net force applied to a body produces a proportional acceleration. In other words, if a body is accelerating, then there is a force on it.

Consistent with the first law, the time derivative of the momentum is non-zero when the momentum changes direction, even if there is no change in its magnitude; such is the case with uniform circular motion. The relationship also implies the conservation of momentum: when the net force on the body is zero, the momentum of the body is constant. Any net force is equal to the rate of change of the momentum.

Any mass that is gained or lost by the system will cause a change in momentum that is not the result of an external force. A different equation is necessary for variable-mass systems (see below).

Newton’s second law requires modification if the effects of special relativity are to be taken into account, because at high speeds the approximation that momentum is the product of rest mass and velocity is not accurate.

Impulse

An impulse J occurs when a force F acts over an interval of time Δt, and it is given by[22][23]

Since force is the time derivative of momentum, it follows that

This relation between impulse and momentum is closer to Newton’s wording of the second law.[24]

Impulse is a concept frequently used in the analysis of collisions and impacts.[25]

Variable-mass systems

Main article: Variable-mass system

Variable-mass systems, like a rocket burning fuel and ejecting spent gases, are not closed and cannot be directly treated by making mass a function of time in the second law;[20] that is, the following formula is wrong:[21]

The falsehood of this formula can be seen by noting that it does not respect Galilean invariance: a variable-mass object with F = 0 in one frame will be seen to have F ≠ 0 in another frame.[19]

The correct equation of motion for a body whose mass m varies with time by either ejecting or accreting mass is obtained by applying the second law to the entire, constant-mass system consisting of the body and its ejected/accreted mass; the result is[19]

where u is the relative velocity of the escaping or incoming mass as seen by the body. From this equation one can derive the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation.

Under some conventions, the quantity u dm/dt on the left-hand side, known as the thrust, is defined as a force (the force exerted on the body by the changing mass, such as rocket exhaust) and is included in the quantity F. Then, by substituting the definition of acceleration, the equation becomes F = ma.

History

Newton’s original Latin reads:

“ |

Lex II: Mutationem motus proportionalem esse vi motrici impressae, et fieri secundum lineam rectam qua vis illa imprimitur. |

” |

This was translated quite closely in Motte’s 1729 translation as:

“ |

Law II: The alteration of motion is ever proportional to the motive force impress’d; and is made in the direction of the right line in which that force is impress’d. |

” |

According to modern ideas of how Newton was using his terminology,[26] this is understood, in modern terms, as an equivalent of:

The change of momentum of a body is proportional to the impulse impressed on the body, and happens along the straight line on which that impulse is impressed.

Motte’s 1729 translation of Newton’s Latin continued with Newton’s commentary on the second law of motion, reading:

If a force generates a motion, a double force will generate double the motion, a triple force triple the motion, whether that force be impressed altogether and at once, or gradually and successively. And this motion (being always directed the same way with the generating force), if the body moved before, is added to or subtracted from the former motion, according as they directly conspire with or are directly contrary to each other; or obliquely joined, when they are oblique, so as to produce a new motion compounded from the determination of both.

The sense or senses in which Newton used his terminology, and how he understood the second law and intended it to be understood, have been extensively discussed by historians of science, along with the relations between Newton’s formulation and modern formulations.[27]

Newton’s third law

An illustration of Newton’s third law in which two skaters push against each other. The skater on the left exerts a force F on the skater on the right, and the skater on the right exerts a force −Fon the skater on the right.

Although the forces are equal, the accelerations are not: the less massive skater will have a greater acceleration due to Newton’s second law.

A description of Newton’s third law and contact forces[28]

The third law states that all forces exist in pairs: if one object A exerts a force FA on a second object B, then B simultaneously exerts a force FB on A, and the two forces are equal and opposite: FA = −FB.[29] The third law means that all forces are interactions between different bodies,[30][31] and thus that there is no such thing as a unidirectional force or a force that acts on only one body. This law is sometimes referred to as the action-reaction law, with FA called the “action” and FB the “reaction”. The action and the reaction are simultaneous, and it does not matter which is called the action and which is called reaction; both forces are part of a single interaction, and neither force exists without the other.[29]

The two forces in Newton’s third law are of the same type (e.g., if the road exerts a forward frictional force on an accelerating car’s tires, then it is also a frictional force that Newton’s third law predicts for the tires pushing backward on the road).

From a conceptual standpoint, Newton’s third law is seen when a person walks: they push against the floor, and the floor pushes against the person. Similarly, the tires of a car push against the road while the road pushes back on the tires—the tires and road simultaneously push against each other. In swimming, a person interacts with the water, pushing the water backward, while the water simultaneously pushes the person forward—both the person and the water push against each other. The reaction forces account for the motion in these examples. These forces depend on friction; a person or car on ice, for example, may be unable to exert the action force to produce the needed reaction force.[32]

History

“ |

Lex III: Actioni contrariam semper et æqualem esse reactionem: sive corporum duorum actiones in se mutuo semper esse æquales et in partes contrarias dirigi. |

” |

“ |

Law III: To every action there is always an equal and opposite reaction: or the forces of two bodies on each other are always equal and are directed in opposite directions. |

” |

A more direct translation than the one just given above is:

LAW III: To every action there is always opposed an equal reaction: or the mutual actions of two bodies upon each other are always equal, and directed to contrary parts. — Whatever draws or presses another is as much drawn or pressed by that other. If you press a stone with your finger, the finger is also pressed by the stone. If a horse draws a stone tied to a rope, the horse (if I may so say) will be equally drawn back towards the stone: for the distended rope, by the same endeavour to relax or unbend itself, will draw the horse as much towards the stone, as it does the stone towards the horse, and will obstruct the progress of the one as much as it advances that of the other. If a body impinges upon another, and by its force changes the motion of the other, that body also (because of the equality of the mutual pressure) will undergo an equal change, in its own motion, toward the contrary part. The changes made by these actions are equal, not in the velocities but in the motions of the bodies; that is to say, if the bodies are not hindered by any other impediments. For, as the motions are equally changed, the changes of the velocities made toward contrary parts are reciprocally proportional to the bodies. This law takes place also in attractions, as will be proved in the next scholium.[33]

In the above, as usual, motion is Newton’s name for momentum, hence his careful distinction between motion and velocity.

Newton used the third law to derive the law of conservation of momentum;[34] however from a deeper perspective, conservation of momentum is the more fundamental idea (derived via Noether’s theorem from Galilean invariance), and holds in cases where Newton’s third law appears to fail, for instance when force fields as well as particles carry momentum, and in quantum mechanics.

Importance and range of validity

Newton’s laws were verified by experiment and observation for over 200 years, and they are excellent approximations at the scales and speeds of everyday life. Newton’s laws of motion, together with his law of universal gravitation and the mathematical techniques of calculus, provided for the first time a unified quantitative explanation for a wide range of physical phenomena.

These three laws hold to a good approximation for macroscopic objects under everyday conditions. However, Newton’s laws (combined with universal gravitation and classical electrodynamics) are inappropriate for use in certain circumstances, most notably at very small scales, very high speeds (in special relativity, the Lorentz factor must be included in the expression for momentum along with rest mass and velocity) or very strong gravitational fields. Therefore, the laws cannot be used to explain phenomena such as conduction of electricity in a semiconductor, optical properties of substances, errors in non-relativistically corrected GPS systems and superconductivity. Explanation of these phenomena requires more sophisticated physical theories, including general relativity and quantum field theory.

In quantum mechanics concepts such as force, momentum, and position are defined by linear operators that operate on the quantum state; at speeds that are much lower than the speed of light, Newton’s laws are just as exact for these operators as they are for classical objects. At speeds comparable to the speed of light, the second law holds in the original form F = dp/dt, where F and p are four-vectors.

Relationship to the conservation laws

In modern physics, the laws of conservation of momentum, energy, and angular momentum are of more general validity than Newton’s laws, since they apply to both light and matter, and to both classical and non-classical physics.

This can be stated simply, “Momentum, energy and angular momentum cannot be created or destroyed.”

Because force is the time derivative of momentum, the concept of force is redundant and subordinate to the conservation of momentum, and is not used in fundamental theories (e.g., quantum mechanics,quantum electrodynamics, general relativity, etc.). The standard model explains in detail how the three fundamental forces known as gauge forces originate out of exchange by virtual particles. Other forces such as gravity and fermionic degeneracy pressure also arise from the momentum conservation. Indeed, the conservation of 4-momentum in inertial motion via curved space-time results in what we callgravitational force in general relativity theory. Application of space derivative (which is a momentum operator in quantum mechanics) to overlapping wave functions of pair of fermions (particles with half-integerspin) results in shifts of maxima of compound wavefunction away from each other, which is observable as “repulsion” of fermions.

Newton stated the third law within a world-view that assumed instantaneous action at a distance between material particles. However, he was prepared for philosophical criticism of this action at a distance, and it was in this context that he stated the famous phrase “I feign no hypotheses“. In modern physics, action at a distance has been completely eliminated, except for subtle effects involving quantum entanglement.[citation needed] However in modern engineering in all practical applications involving the motion of vehicles and satellites, the concept of action at a distance is used extensively.

The discovery of the Second Law of Thermodynamics by Carnot in the 19th century showed that every physical quantity is not conserved over time, thus disproving the validity of inducing the opposite metaphysical view from Newton’s laws. Hence, a “steady-state” worldview based solely on Newton’s laws and the conservation laws does not take entropy into account.

See also

|

|

|

Wikipedia books are collections of articles that can be downloaded or ordered in print. |

|

-

Euler’s laws

-

Galilean invariance

-

Hamiltonian mechanics

-

Lagrangian mechanics

-

List of scientific laws named after people

-

Mercury, orbit of

-

Modified Newtonian dynamics

-

Newton’s law of universal gravitation

-

Principle of least action

-

Reaction (physics)

References and notes

-

^ For explanations of Newton’s laws of motion by Newton in the early 18th century, by the physicist William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) in the mid-19th century, and by a modern text of the early 21st century, see:-^ Halliday

- Newton’s “Axioms or Laws of Motion” starting on page 19 of volume 1 of the 1729 translation of the “Principia“;

- Section 242, Newton’s laws of motion in Thomson, W (Lord Kelvin), and Tait, P G, (1867), Treatise on natural philosophy, volume 1; and

- Benjamin Crowell (2000), Newtonian Physics.

-

^ Browne, Michael E. (1999-07) (Series: Schaum’s Outline Series). Schaum’s outline of theory and problems of physics for engineering and science. McGraw-Hill Companies. pp. 58.ISBN 978-0-07-008498-8.

-

^ Holzner, Steven (2005-12). Physics for Dummies. Wiley, John & Sons, Incorporated. pp. 64. ISBN 978-0-7645-5433-9.

-

^ See the Principia on line at Andrew Motte Translation

-

^ Andrew Motte translation of Newton’s Principia (1687) Axioms or Laws of Motion

-

^ [...]while Newton had used the word ‘body’ vaguely and in at least three different meanings, Euler realized that the statements of Newton are generally correct only when applied to masses concentrated at isolated points;Truesdell, Clifford A.; Becchi, Antonio; Benvenuto, Edoardo (2003). Essays on the history of mechanics: in memory of Clifford Ambrose Truesdell and Edoardo Benvenuto. New York: Birkhäuser. p. 207. ISBN 3-7643-1476-1.

-

^ Lubliner, Jacob (2008). Plasticity Theory (Revised Edition). Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-46290-0.

-

^ a b Galili, I.; Tseitlin, M. (2003). “Newton’s First Law: Text, Translations, Interpretations and Physics Education”. Science & Education 12 (1): 45–73. Bibcode 2003Sc&Ed..12…45G.doi:10.1023/A:1022632600805.

-

^ Benjamin Crowell. “4. Force and Motion”. Newtonian Physics. ISBN 0-9704670-1-X.

-

^ In making a modern adjustment of the second law for (some of) the effects of relativity, m would be treated as the relativistic mass, producing the relativistic expression for momentum, and the third law might be modified if possible to allow for the finite signal propagation speed between distant interacting particles.

-

^ Walter Lewin (September 20, 1999) (in English) (ogg).Newton’s First, Second, and Third Laws. MIT Course 8.01: Classical Mechanics, Lecture 6. (videotape). Cambridge, MA USA: MIT OCW. Event occurs at 0:00–6:53. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

-

^ NMJ Woodhouse (2003). Special relativity. London/Berlin: Springer. p. 6. ISBN 1-85233-426-6.

-

^ Beatty, Millard F. (2006). Principles of engineering mechanics Volume 2 of Principles of Engineering Mechanics: Dynamics-The Analysis of Motion,. Springer. p. 24. ISBN 0-387-23704-6.

-

^ Thornton, Marion (2004). Classical dynamics of particles and systems (5th ed.). Brooks/Cole. p. 53. ISBN 0-534-40896-6.

-

^ Isaac Newton, The Principia, A new translation by I.B. Cohen and A. Whitman, University of California press, Berkeley 1999.

-

^ Thomas Hobbes wrote in Leviathan:

That when a thing lies still, unless somewhat else stir it, it will lie still forever, is a truth that no man doubts. But [the proposition] that when a thing is in motion it will eternally be in motion unless somewhat else stay it, though the reason be the same (namely that nothing can change itself), is not so easily assented to. For men measure not only other men but all other things by themselves. And because they find themselves subject after motion to pain and lassitude, [they] think every thing else grows weary of motion and seeks repose of its own accord, little considering whether it be not some other motion wherein that desire of rest they find in themselves, consists.

-

^ Lewin, Newton’s First, Second, and Third Laws, Lecture 6. (6:53–11:06)

-

^ a b c Plastino, Angel R.; Muzzio, Juan C. (1992). “On the use and abuse of Newton’s second law for variable mass problems”. Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy(Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers) 53 (3): 227–232.Bibcode 1992CeMDA..53..227P. doi:10.1007/BF00052611.ISSN 0923-2958. ”We may conclude emphasizing that Newton’s second law is valid for constant mass only. When the mass varies due to accretion or ablation, [an alternate equation explicitly accounting for the changing mass] should be used.”

-

^ a b Halliday; Resnick. Physics. 1. pp. 199. ISBN 0-471-03710-9. “It is important to note that we cannot derive a general expression for Newton’s second law for variable mass systems by treating the mass in F = dP/dt = d(Mv) as a variable. [...] Wecan use F = dP/dt to analyze variable mass systems only if we apply it to an entire system of constant mass having parts among which there is an interchange of mass.” [Emphasis as in the original]

-

^ a b Kleppner, Daniel; Robert Kolenkow (1973). An Introduction to Mechanics. McGraw-Hill. pp. 133–134. ISBN 0-07-035048-5. “Recall that F = dP/dt was established for a system composed of a certain set of particles[. ... I]t is essential to deal with the same set of particles throughout the time interval[. ...] Consequently, the mass of the system can not change during the time of interest.”

-

^ Hannah, J, Hillier, M J, Applied Mechanics, p221, Pitman Paperbacks, 1971

-

^ Raymond A. Serway, Jerry S. Faughn (2006). College Physics. Pacific Grove CA: Thompson-Brooks/Cole. p. 161.ISBN 0-534-99724-4.

-

^ I Bernard Cohen (Peter M. Harman & Alan E. Shapiro, Eds) (2002). The investigation of difficult things: essays on Newton and the history of the exact sciences in honour of D.T. Whiteside. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 353. ISBN 0-521-89266-X.

-

^ WJ Stronge (2004). Impact mechanics. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 12 ff. ISBN 0-521-60289-0.

-

^ According to Maxwell in Matter and Motion, Newton meant bymotion ”the quantity of matter moved as well as the rate at which it travels” and by impressed force he meant “the time during which the force acts as well as the intensity of the force“. See Harman and Shapiro, cited below.

-

^ See for example (1) I Bernard Cohen, “Newton’s Second Law and the Concept of Force in the Principia”, in “The Annus Mirabilis of Sir Isaac Newton 1666–1966″ (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1967), pages 143–185; (2) Stuart Pierson, “‘Corpore cadente. . .’: Historians Discuss Newton’s Second Law”, Perspectives on Science, 1 (1993), pages 627–658; and (3) Bruce Pourciau, “Newton’s Interpretation of Newton’s Second Law”, Archive for History of Exact Sciences, vol.60 (2006), pages 157–207; also an online discussion by G E Smith, in 5. Newton’s Laws of Motion, s.5 of “Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica” in (online) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2007.

-

^ Lewin, Newton’s First, Second, and Third Laws, Lecture 6. (14:11–16:00)

-

^ a b Resnick; Halliday; Krane (1992). Physics, Volume 1 (4th ed.). p. 83.

-

^ C Hellingman (1992). “Newton’s third law revisited”. Phys. Educ. 27 (2): 112–115. Bibcode 1992PhyEd..27..112H.doi:10.1088/0031-9120/27/2/011. “Quoting Newton in thePrincipia: It is not one action by which the Sun attracts Jupiter, and another by which Jupiter attracts the Sun; but it is one action by which the Sun and Jupiter mutually endeavour to come nearer together.”

-

^ Resnick and Halliday (1977). “Physics”. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 78–79. “Any single force is only one aspect of a mutual interaction between two bodies.”

-

^ Hewitt (2006), p. 75

-

^ This translation of the third law and the commentary following it can be found in the “Principia” on page 20 of volume 1 of the 1729 translation.

-

^ Newton, Principia, Corollary III to the laws of motion

![\mathbf{F}_\mathrm{net} = \frac{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{d}t}\big[m(t)\mathbf{v}(t)\big] = m(t) \frac{\mathrm{d}\mathbf{v}}{\mathrm{d}t} + \mathbf{v}(t) \frac{\mathrm{d}m}{\mathrm{d}t}. \qquad \mathrm{(wrong)}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/4/5/f/45f0d6b5ec0038d6bad24d85274e027c.png)